Uncertainty principle

| Quantum mechanics | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Uncertainty principle |

||||||||||||||||

Introduction · Mathematical formulations

|

||||||||||||||||

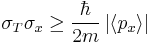

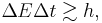

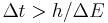

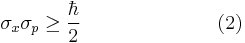

In quantum mechanics, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle states by precise inequalities that certain pairs of physical properties, such as position and momentum, cannot be simultaneously known to arbitrarily high precision. That is, the more precisely one property is measured, the less precisely the other can be measured. The principle states that a minimum exists for the product of the uncertainties in these properties that is equal to or greater than one half of the reduced Planck's constant (ħ = h/2π).

Published by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, the principle means that it is impossible to determine simultaneously both the position and velocity of an electron or any other particle with any great degree of accuracy or certainty. Moreover, his principle is not a statement about the limitations of a researcher's ability to measure particular quantities of a system, but it is a statement about the nature of the system itself as described by the equations of quantum mechanics.

In quantum physics, a particle is described by a wave packet, which gives rise to this phenomenon. Consider the measurement of the position of a particle. It could be anywhere the particle's wave packet has non-zero amplitude, meaning the position is uncertain – it could be almost anywhere along the wave packet. To obtain an accurate reading of position, this wave packet must be 'compressed' as much as possible, meaning it must be made up of increasing numbers of sine waves added together. The momentum of the particle is proportional to the wavelength of one of these waves, but it could be any of them. So a more precise position measurement–by adding together more waves–means the momentum measurement becomes less precise (and vice versa).

The only kind of wave with a definite position is concentrated at one point, and such a wave has an indefinite wavelength (and therefore an indefinite momentum). Conversely, the only kind of wave with a definite wavelength is an infinite regular periodic oscillation over all space, which has no definite position. So in quantum mechanics, there can be no states that describe a particle with both a definite position and a definite momentum. The more precise the position, the less precise the momentum.

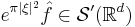

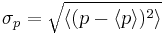

A mathematical statement of the principle is that every quantum state has the property that the root mean square (RMS) deviation of the position from its mean (the standard deviation of the x-distribution):

times the RMS deviation of the momentum from its mean (the standard deviation of p):

can never be smaller than a fixed fraction of Planck's constant:

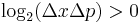

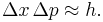

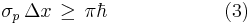

The uncertainty principle can be restated in terms of other measurement processes, which involves collapse of the wavefunction. When the position is initially localized by preparation, the wavefunction collapses to a narrow bump in an interval  , and the momentum wavefunction becomes spread out. The particle's momentum is left uncertain by an amount inversely proportional to the accuracy of the position measurement:

, and the momentum wavefunction becomes spread out. The particle's momentum is left uncertain by an amount inversely proportional to the accuracy of the position measurement:

-

-

.

.

-

If the initial preparation in  is understood as an observation or disturbance of the particles then this means that the uncertainty principle is related to the observer effect. However, this is not true in the case of the measurement process corresponding to the former inequality but only for the latter inequality.

is understood as an observation or disturbance of the particles then this means that the uncertainty principle is related to the observer effect. However, this is not true in the case of the measurement process corresponding to the former inequality but only for the latter inequality.

Historical introduction

Werner Heisenberg formulated the uncertainty principle in Niels Bohr's institute at Copenhagen, while working on the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics.

In 1925, following pioneering work with Hendrik Kramers, Heisenberg developed matrix mechanics, which replaced the ad-hoc old quantum theory with modern quantum mechanics. The central assumption was that the classical motion was not precise at the quantum level, and electrons in an atom did not travel on sharply defined orbits. Rather, the motion was smeared out in a strange way: the Fourier transform of time only involving those frequencies that could be seen in quantum jumps.

Heisenberg's paper did not admit any unobservable quantities like the exact position of the electron in an orbit at any time; he only allowed the theorist to talk about the Fourier components of the motion. Since the Fourier components were not defined at the classical frequencies, they could not be used to construct an exact trajectory, so that the formalism could not answer certain overly precise questions about where the electron was or how fast it was going.

The most striking property of Heisenberg's infinite matrices for the position and momentum is that they do not commute. Heisenberg's canonical commutation relation indicates by how much:

-

-

![[X,P] = X P - P X = i \hbar](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/0342ffe593429f253ff09a217ad29be5.png) (see derivations below)

(see derivations below)

-

and this result did not have a clear physical interpretation in the beginning.

In March 1926, working in Bohr's institute, Heisenberg realized that the non-commutativity implies the uncertainty principle. This was a clear physical interpretation for the non-commutativity, and it laid the foundation for what became known as the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. Heisenberg showed that the commutation relation implies an uncertainty, or in Bohr's language a complementarity.[1] Any two variables that do not commute cannot be measured simultaneously—the more precisely one is known, the less precisely the other can be known.

One way to understand the complementarity between position and momentum is by wave-particle duality. If a particle described by a plane wave passes through a narrow slit in a wall like a water-wave passing through a narrow channel, the particle diffracts and its wave comes out in a range of angles. The narrower the slit, the wider the diffracted wave and the greater the uncertainty in momentum afterwards. The laws of diffraction require that the spread in angle  is about

is about  , where

, where  is the slit width and

is the slit width and  is the wavelength. From the de Broglie relation, the size of the slit and the range in momentum of the diffracted wave are related by Heisenberg's rule:

is the wavelength. From the de Broglie relation, the size of the slit and the range in momentum of the diffracted wave are related by Heisenberg's rule:

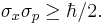

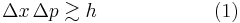

In his celebrated paper (1927), Heisenberg established this expression as the minimum amount of unavoidable momentum disturbance caused by any position measurement,[2] but he did not give a precise definition for the uncertainties Δx and Δp. Instead, he gave some plausible estimates in each case separately. In his Chicago lecture[3] he refined his principle:

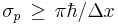

But it was Kennard[4] in 1927 who first proved the modern inequality:

where  , and σx, σp are the standard deviations of position and momentum. Heisenberg himself only proved relation (2) for the special case of Gaussian states.[3] However, it should be noted that

, and σx, σp are the standard deviations of position and momentum. Heisenberg himself only proved relation (2) for the special case of Gaussian states.[3] However, it should be noted that  and

and  are not the same quantities.

are not the same quantities.  and

and  as defined in Kennard, are obtained by making repeated measurements of position on an ensemble of systems and by making repeated measurements of momentum on an ensemble of systems and calculating the standard deviation of those measurements. The Kennard expression, therefore says nothing about the simultaneous measurement of position and momentum.

as defined in Kennard, are obtained by making repeated measurements of position on an ensemble of systems and by making repeated measurements of momentum on an ensemble of systems and calculating the standard deviation of those measurements. The Kennard expression, therefore says nothing about the simultaneous measurement of position and momentum.

A rigorous proof of a new inequality for simultaneous measurements in the spirit of Heisenberg and Bohr has been given recently. The measurement process is as follows: Whenever a particle is localized in a finite interval  , then the standard deviation of its momentum satisfies

, then the standard deviation of its momentum satisfies

while the equal sign is given for Cosine states.[5]

Heisenberg's microscope

One way in which Heisenberg originally argued for the uncertainty principle is by using an imaginary microscope as a measuring device.[3] He imagines an experimenter trying to measure the position and momentum of an electron by shooting a photon at it.

If the photon has a short wavelength, and therefore a large momentum, the position can be measured accurately. But the photon scatters in a random direction, transferring a large and uncertain amount of momentum to the electron. If the photon has a long wavelength and low momentum, the collision doesn't disturb the electron's momentum very much, but the scattering will reveal its position only vaguely.

If a large aperture is used for the microscope, the electron's location can be well resolved (see Rayleigh criterion); but by the principle of conservation of momentum, the transverse momentum of the incoming photon and hence the new momentum of the electron resolves poorly. If a small aperture is used, the accuracy of the two resolutions is the other way around.

The trade-offs imply that no matter what photon wavelength and aperture size are used, the product of the uncertainty in measured position and measured momentum is greater than or equal to a lower bound, which is up to a small numerical factor equal to Planck's constant.[6] Heisenberg did not care to formulate the uncertainty principle as an exact bound, and preferred to use it as a heuristic quantitative statement, correct up to small numerical factors.

Critical reactions

The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics and Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle were in fact seen as twin targets by detractors who believed in an underlying determinism and realism. Within the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, there is no fundamental reality the quantum state describes, just a prescription for calculating experimental results. There is no way to say what the state of a system fundamentally is, only what the result of observations might be.

Albert Einstein believed that randomness is a reflection of our ignorance of some fundamental property of reality, while Niels Bohr believed that the probability distributions are fundamental and irreducible, and depend on which measurements we choose to perform. Einstein and Bohr debated the uncertainty principle for many years.

Einstein's slit

The first of Einstein's thought experiments challenging the uncertainty principle went as follows:

- Consider a particle passing through a slit of width d. The slit introduces an uncertainty in momentum of approximately h/d because the particle passes through the wall. But let us determine the momentum of the particle by measuring the recoil of the wall. In doing so, we find the momentum of the particle to arbitrary accuracy by conservation of momentum.

Bohr's response was that the wall is quantum mechanical as well, and that to measure the recoil to accuracy  the momentum of the wall must be known to this accuracy before the particle passes through. This introduces an uncertainty in the position of the wall and therefore the position of the slit equal to

the momentum of the wall must be known to this accuracy before the particle passes through. This introduces an uncertainty in the position of the wall and therefore the position of the slit equal to  , and if the wall's momentum is known precisely enough to measure the recoil, the slit's position is uncertain enough to disallow a position measurement.

, and if the wall's momentum is known precisely enough to measure the recoil, the slit's position is uncertain enough to disallow a position measurement.

A similar analysis with particles diffracting through multiple slits is given by Richard Feynman[7].

Einstein's box

Another of Einstein's thought experiments (Einstein's box) was designed to challenge the time/energy uncertainty principle. It is very similar to the slit experiment in space, except here the narrow window the particle passes through is in time:

- Consider a box filled with light. The box has a shutter that a clock opens and quickly closes at a precise time, and some of the light escapes. We can set the clock so that the time that the energy escapes is known. To measure the amount of energy that leaves, Einstein proposed weighing the box just after the emission. The missing energy lessens the weight of the box. If the box is mounted on a scale, it is naively possible to adjust the parameters so that the uncertainty principle is violated.

Bohr spent a day considering this setup, but eventually realized that if the energy of the box is precisely known, the time the shutter opens at is uncertain. If the case, scale, and box are in a gravitational field then, in some cases, it is the uncertainty of the position of the clock in the gravitational field that alters the ticking rate. This can introduce the right amount of uncertainty. This was ironic as it was Einstein himself who first discovered gravity's effect on clocks.

EPR measurements

Bohr was compelled to modify his understanding of the uncertainty principle after another thought experiment by Einstein. In 1935, Einstein, Podolski and Rosen (see EPR paradox) published an analysis of widely separated entangled particles. Measuring one particle, Einstein realized, would alter the probability distribution of the other, yet here the other particle could not possibly be disturbed. This example led Bohr to revise his understanding of the principle, concluding that the uncertainty was not caused by a direct interaction.[8]

But Einstein came to much more far-reaching conclusions from the same thought experiment. He believed as "natural basic assumption" that a complete description of reality would have to predict the results of experiments from "locally changing deterministic quantities", and therefore would have to include more information than the maximum possible allowed by the uncertainty principle.

In 1964 John Bell showed that this assumption can be falsified, since it would imply a certain inequality between the probabilities of different experiments. Experimental results confirm the predictions of quantum mechanics, ruling out Einstein's basic assumption that led him to the suggestion of his hidden variables. (Ironically this is one of the best examples for Karl Popper's philosophy of invalidation of a theory by falsification-experiments; i.e. here Einstein's "basic assumption" became falsified by experiments based on Bell's inequalities; for the objections of Karl Popper against the Heisenberg inequality itself, see below.)

While it is possible to assume that quantum mechanical predictions are due to nonlocal hidden variables, and in fact David Bohm invented such a formulation, this is not a satisfactory resolution for the vast majority of physicists. The question of whether a random outcome is predetermined by a nonlocal theory can be philosophical, and potentially intractable. If the hidden variables are not constrained, they could just be a list of random digits that are used to produce the measurement outcomes. To make it sensible, the assumption of nonlocal hidden variables is sometimes augmented by a second assumption — that the size of the observable universe puts a limit on the computations that these variables can do. A nonlocal theory of this sort predicts that a quantum computer encounters fundamental obstacles when it tries to factor numbers of approximately 10,000 digits or more; an achievable task in quantum mechanics.[9]

Popper's criticism

Karl Popper criticized Heisenberg's form of the uncertainty principle, that a measurement of position disturbs the momentum, based on the following observation: if a particle with definite momentum passes through a narrow slit, the diffracted wave has some amplitude to go in the original direction of motion. If the momentum of the particle is measured after it goes through the slit, there is always some probability, however small, that the momentum will be the same as it was before.

Popper thinks of these rare events as falsifications of the uncertainty principle in Heisenberg's original formulation. To preserve the principle, he concludes that Heisenberg's relation does not apply to individual particles or measurements, but only to many identically prepared particles, called ensembles. Popper's criticism applies to nearly all probabilistic theories, since a probabilistic statement requires many measurements to either verify or falsify.

Popper's criticism does not trouble physicists who subscribe to the Copenhagen interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Popper's presumption is that the measurement is revealing some preexisting information about the particle, the momentum, which the particle already possesses. According to Copenhagen interpretation the quantum mechanical description of the wavefunction is not a reflection of ignorance about the values of some more fundamental quantities, it is the complete description of the state of the particle. In this philosophical view, Popper's example is not a falsification, since after the particle diffracts through the slit and before the momentum is measured, the wavefunction is changed so that the momentum is still as uncertain as the principle demands.

Mathematical derivations

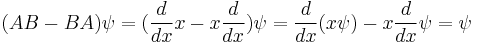

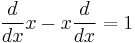

When linear operators A and B act on a function  , they don't always commute. A clear example is when operator B multiplies by x, while operator A takes the derivative with respect to x. Then, for every wave function

, they don't always commute. A clear example is when operator B multiplies by x, while operator A takes the derivative with respect to x. Then, for every wave function  we can write

we can write

which in operator language means that

This example is important, because it is very close to the canonical commutation relation of quantum mechanics. There, the position operator multiplies the value of the wavefunction by x, while the corresponding momentum operator differentiates and multiplies by  , so that:

, so that:

It is the nonzero commutator that implies the uncertainty.

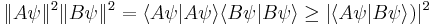

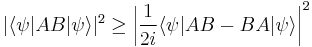

For any two operators A and B:

which is a statement of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality for the inner product of the two vectors  and

and  . On the other hand, the expectation value of the product AB is always greater than the magnitude of its imaginary part:

. On the other hand, the expectation value of the product AB is always greater than the magnitude of its imaginary part:

and putting the two inequalities together for Hermitian operators gives the relation:

and the uncertainty principle is a special case.

Physical Interpretation

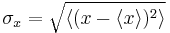

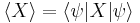

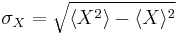

The inequality above acquires its dispersion interpretation:

where

is the mean of observable X in the state  and

and

is the corresponding standard deviation of observable X.

By substituting  for A and

for A and  for B in the general operator norm inequality, since the imaginary part of the product, the commutator is unaffected by the shift:

for B in the general operator norm inequality, since the imaginary part of the product, the commutator is unaffected by the shift:

The big side of the inequality is the product of the norms of  and

and  , which in quantum mechanics are the standard deviations of A and B. The small side is the norm of the commutator, which for the position and momentum is just

, which in quantum mechanics are the standard deviations of A and B. The small side is the norm of the commutator, which for the position and momentum is just  .

.

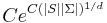

A further generalization is due to Schrödinger: Given any two Hermitian operators A and B, and a system in the state ψ, there are probability distributions for the value of a measurement of A and B, with standard deviations  and

and  . Then

. Then

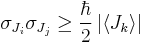

where [A, B] = AB − BA is the commutator of A and B,  = AB+BA is the anticommutator. This inequality is sometimes called the Robertson–Schrödinger relation, and includes the Heisenberg uncertainty principle as a special case but for a different measurement process. The inequality with the commutator term only was developed in 1930 by Howard Percy Robertson, and Erwin Schrödinger added the anticommutator term a little later.

= AB+BA is the anticommutator. This inequality is sometimes called the Robertson–Schrödinger relation, and includes the Heisenberg uncertainty principle as a special case but for a different measurement process. The inequality with the commutator term only was developed in 1930 by Howard Percy Robertson, and Erwin Schrödinger added the anticommutator term a little later.

Examples

The Robertson-Schrödinger relation gives the uncertainty relation for any two observables that do not commute:

- between position and momentum by applying the commutator relation

![[x,p_x]=i\hbar](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/a54264a655e2e824a033aa70f53e51d5.png) :

:

- between the kinetic energy T and position x of a particle :

- between two orthogonal components of the total angular momentum operator of an object:

-

- where i, j, k are distinct and Ji denotes angular momentum along the xi axis. This relation implies that only a single component of a system's angular momentum can be defined with arbitrary precision, normally the component parallel to an external (magnetic or electric) field.

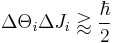

- between angular position and angular momentum of an object with small angular uncertainty:

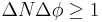

- between the number of electrons in a superconductor and the phase of its Ginzburg–Landau order parameter[10][11]

Energy-time uncertainty principle

One well-known uncertainty relation is not an obvious consequence of the Robertson–Schrödinger relation: the energy-time uncertainty principle.

Since energy bears the same relation to time as momentum does to space in special relativity, it was clear to many early founders, Niels Bohr among them, that the following relation holds:[2][3]

but it was not always obvious what Δt was, because the time at which the particle has a given state is not an operator belonging to the particle, it is a parameter describing the evolution of the system. As Lev Landau once joked "To violate the time-energy uncertainty relation all I have to do is measure the energy very precisely and then look at my watch!"

Nevertheless, Einstein and Bohr understood the heuristic meaning of the principle. A state that only exists for a short time cannot have a definite energy. To have a definite energy, the frequency of the state must accurately be defined, and this requires the state to hang around for many cycles, the reciprocal of the required accuracy.

For example, in spectroscopy, excited states have a finite lifetime. By the time-energy uncertainty principle, they do not have a definite energy, and each time they decay the energy they release is slightly different. The average energy of the outgoing photon has a peak at the theoretical energy of the state, but the distribution has a finite width called the natural linewidth. Fast-decaying states have a broad linewidth, while slow decaying states have a narrow linewidth.

The broad linewidth of fast decaying states makes it difficult to accurately measure the energy of the state, and researchers have even used microwave cavities to slow down the decay-rate, to get sharper peaks[12]. The same linewidth effect also makes it difficult to measure the rest mass of fast decaying particles in particle physics. The faster the particle decays, the less certain is its mass.

One false formulation of the energy-time uncertainty principle says that measuring the energy of a quantum system to an accuracy  requires a time interval

requires a time interval  . This formulation is similar to the one alluded to in Landau's joke, and was explicitly invalidated by Y. Aharonov and D. Bohm in 1961. The time

. This formulation is similar to the one alluded to in Landau's joke, and was explicitly invalidated by Y. Aharonov and D. Bohm in 1961. The time  in the uncertainty relation is the time during which the system exists unperturbed, not the time during which the experimental equipment is turned on.

in the uncertainty relation is the time during which the system exists unperturbed, not the time during which the experimental equipment is turned on.

Another common misconception is that the energy-time uncertainty principle says that the conservation of energy can be temporarily violated – energy can be "borrowed" from the Universe as long as it is "returned" within a short amount of time.[13] Although this agrees with the spirit of relativistic quantum mechanics, it is based on the false axiom that the energy of the Universe is an exactly known parameter at all times. More accurately, when events transpire at shorter time intervals, there is a greater uncertainty in the energy of these events. Therefore it is not that the conservation of energy is violated when quantum field theory uses temporary electron-positron pairs in its calculations, but that the energy of quantum systems is not known with enough precision to limit their behavior to a single, simple history. Thus the influence of all histories must be incorporated into quantum calculations, including those with much greater or much less energy than the mean of the measured/calculated energy distribution.

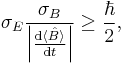

In 1936 Dirac offered a precise definition and derivation of the time-energy uncertainty relation in a relativistic quantum theory of "events". But a better-known, more widely used formulation of the time-energy uncertainty principle was given in 1945 by L. I. Mandelshtam and I. E. Tamm, as follows.[14] For a quantum system in a non-stationary state  and an observable

and an observable  represented by a self-adjoint operator

represented by a self-adjoint operator  , the following formula holds:

, the following formula holds:

where  is the standard deviation of the energy operator in the state

is the standard deviation of the energy operator in the state  ,

,  stands for the standard deviation of

stands for the standard deviation of  . Although, the second factor in the left-hand side has dimension of time, it is different from the time parameter that enters Schrödinger equation. It is a lifetime of the state

. Although, the second factor in the left-hand side has dimension of time, it is different from the time parameter that enters Schrödinger equation. It is a lifetime of the state  with respect to the observable

with respect to the observable  . In other words, this is the time after which the expectation value

. In other words, this is the time after which the expectation value  changes appreciably.

changes appreciably.

Uncertainty principle and observer effect

The uncertainty principle is often stated this way:

-

- The measurement of position necessarily disturbs a particle's momentum, and vice versa

This makes the uncertainty principle a kind of observer effect.

This explanation is not incorrect, and was used by both Heisenberg and Bohr. But they were working within the philosophical framework of logical positivism. In this way of looking at the world, the true nature of a physical system, inasmuch as it exists, is defined by the answers to the best-possible measurements which can be made in principle. To state this differently, if a certain property of a system cannot be measured beyond a certain level of accuracy (in principle), then this limitation is a limitation of the system and not the limitation of the devices used to make this measurements. So when they made arguments about unavoidable disturbances in any conceivable measurement, it was obvious to them that this uncertainty was a property of the system, not of the devices.

Today, logical positivism has become unfashionable in many cases, so the explanation of the uncertainty principle in terms of observer effect can be misleading. For one, this explanation makes it seem to the non-positivist that the disturbances are not a property of the particle, but a property of the measurement process; the particle secretly does have a definite position and a definite momentum, but the experimental devices we have are not good enough to find out what these are. This interpretation is not compatible with standard quantum mechanics. In quantum mechanics, states that have both definite position and definite momentum at the same time do not exist.

This explanation is misleading in another way, because sometimes it is a failure to measure the particle that produces the disturbance. For example, if a perfect photographic film contains a small hole, and an incident photon is not observed, then its momentum becomes uncertain by a large amount. By not observing the photon, we discover indirectly that it went through the hole, revealing the photon's position.

The third way in which the explanation can be misleading is due to the nonlocal nature of a quantum state. Sometimes, two particles can be entangled, and then a distant measurement can be performed on one of the two. This measurement should not disturb the other particle in any classical sense, but it can sometimes reveal information about the distant particle. This restricts the possible values of position or momentum in strange ways.

Unlike the other examples, a distant measurement will never cause the overall distribution of either position or momentum to change. The distribution only changes if the results of the distant measurement are known. A secret distant measurement has no effect whatsoever on a particle's position or momentum distribution. But the distant measurement of momentum for instance will still reveal new information, which causes the total wavefunction to collapse. This will restrict the distribution of position and momentum, once that classical information has been revealed and transmitted.

For example If two photons are emitted in opposite directions from the decay of positronium, the momenta of the two photons are opposite. By measuring the momentum of one particle, the momentum of the other is determined, making its momentum distribution sharper, and leaving the position just as indeterminate. But unlike a local measurement, this process can never produce more position uncertainty than what was already there. It is only possible to restrict the uncertainties in different ways, with different statistical properties, depending on what property of the distant particle you choose to measure. By restricting the uncertainty in p to be very small by a distant measurement, the remaining uncertainty in x stays large. (This example was actually the basis of Albert Einstein's important suggestion of the EPR paradox in 1935.)

This queer mechanism of quantum mechanics is the basis of quantum cryptography, where the measurement of a value on one of two entangled particles at one location forces, via the uncertainty principle, a property of a distant particle to become indeterminate and hence unmeasurable.

But Heisenberg did not focus on the mathematics of quantum mechanics, he was primarily concerned with establishing that the uncertainty is actually a property of the world — that it is in fact physically impossible to measure the position and momentum of a particle to a precision better than that allowed by quantum mechanics. To do this, he used physical arguments based on the existence of quanta, but not the full quantum mechanical formalism.

This was a surprising prediction of quantum mechanics, and not yet accepted. Many people would have considered it a flaw that there are no states of definite position and momentum. Heisenberg was trying to show this was not a bug, but a feature—a deep, surprising aspect of the universe. To do this, he could not just use the mathematical formalism, because it was the mathematical formalism itself that he was trying to justify.

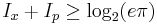

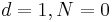

Entropic uncertainty principle

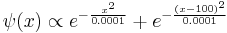

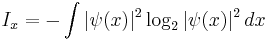

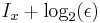

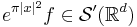

While formulating the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics in 1957, Hugh Everett III discovered a much stronger formulation of the uncertainty principle.[15] In the inequality of standard deviations, some states, like the wavefunction

have a large standard deviation of position, but are actually a superposition of a small number of very narrow bumps. In this case, the momentum uncertainty is much larger than the standard deviation inequality would suggest. A better inequality uses the Shannon information content of the distribution, a measure of the number of bits learned when a random variable described by a probability distribution has a certain value.

The interpretation of I is that the number of bits of information an observer acquires when the value of x is given to accuracy  is equal to

is equal to  . The second part is just the number of bits past the decimal point, the first part is a logarithmic measure of the width of the distribution. For a uniform distribution of width

. The second part is just the number of bits past the decimal point, the first part is a logarithmic measure of the width of the distribution. For a uniform distribution of width  the information content is

the information content is  . This quantity can be negative, which means that the distribution is narrower than one unit, so that learning the first few bits past the decimal point gives no information since they are not uncertain.

. This quantity can be negative, which means that the distribution is narrower than one unit, so that learning the first few bits past the decimal point gives no information since they are not uncertain.

Taking the logarithm of Heisenberg's formulation of uncertainty in natural units.

but the lower bound is not precise.

Everett (and Hirschman[16]) conjectured that for all quantum states:

This was proven by Beckner in 1975.[17]

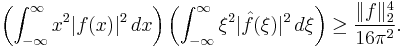

Uncertainty theorems in harmonic analysis

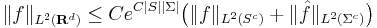

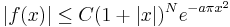

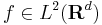

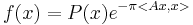

In the context of harmonic analysis, the uncertainty principle implies that one cannot at the same time localize the value of a function and its Fourier transform; to wit, the following inequality holds

Other purely mathematical formulations of uncertainty exist between a function ƒ and its Fourier transform. A variety of such results can be found in (Havin & Jöricke 1994) or (Folland & Sitaram 1997); for a short survey, see (Sitaram 2001).

Benedicks's theorem

Amrein-Berthier (Amrein & Berthier 1977) and Benedicks's theorem (Benedicks 1985) intuitively says that the set of points where ƒ is non-zero and the set of points where  is nonzero cannot both be small. Specifically, it is impossible for a function ƒ in L2(R) and its Fourier transform to both be supported on sets of finite Lebesgue measure. In signal processing, this includes the following well-known result: a function cannot be both time limited and band limited. A more quantitative version is due to Nazarov (Nazarov 1994) and (Jaming 2007):

is nonzero cannot both be small. Specifically, it is impossible for a function ƒ in L2(R) and its Fourier transform to both be supported on sets of finite Lebesgue measure. In signal processing, this includes the following well-known result: a function cannot be both time limited and band limited. A more quantitative version is due to Nazarov (Nazarov 1994) and (Jaming 2007):

One expects that the factor  may be replaced by

may be replaced by  which is only known if either

which is only known if either  or

or  is convex.

is convex.

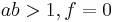

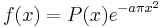

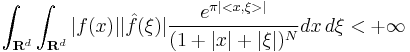

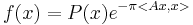

Hardy's uncertainty principle

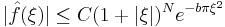

The mathematician G. H. Hardy (Hardy 1933) formulated the following uncertainty principle: it is not possible for ƒ and  to both be "very rapidly decreasing." Specifically, if ƒ is in L2(R), is such that

to both be "very rapidly decreasing." Specifically, if ƒ is in L2(R), is such that  and

and  (

( an integer) then, if

an integer) then, if  while if

while if  then there is a polynomial

then there is a polynomial  of degree

of degree  such that

such that  . This was later improved as follows: if

. This was later improved as follows: if  is such that

is such that  then,

then,  where

where  is a polynomial of degree

is a polynomial of degree  and

and  is a real

is a real  positive definite matrix.

positive definite matrix.

This result was stated in Beurling's complete works without proof and proved in Hörmander (Hörmander 1991) (the case  ) and Bonami–Demange–Jaming (Bonami, Demange & Jaming 2003) for the general case.

) and Bonami–Demange–Jaming (Bonami, Demange & Jaming 2003) for the general case.

Note that Hörmander–Beurling's version implies the case  in Hardy's Theorem while the version by Bonami–Demange–Jaming covers the full strength of Hardy's Theorem. A full description of the case

in Hardy's Theorem while the version by Bonami–Demange–Jaming covers the full strength of Hardy's Theorem. A full description of the case  as well as the following extension to Schwarz class distributions appears in Demange (Demange 2010): if

as well as the following extension to Schwarz class distributions appears in Demange (Demange 2010): if  is such that

is such that  and

and  then

then  where

where  is a polynomial and

is a polynomial and  is a real

is a real  positive definite matrix.

positive definite matrix.

Uncertainty principle of game theory

The uncertainty principle of game theory was formulated by Szekely and Rizzo in 2007.[18] This principle is a lower bound for the entropy of optimal strategies of players in terms of the commutator of two nonlinear operators: minimum and maximum. If the payoff matrix (aij) of an arbitrary zero-sum game is normalized (i.e. the smallest number in this matrix is 0, the biggest number is 1) and the commutator

minj maxi (aij) − maxi minj (aij) = h

then the entropy of the optimal strategy of any of the players cannot be smaller than the entropy of the two-point distribution [1/(1+h), h/(1+h)] and this is the best lower bound. (This is zero if and only if h = 0 i.e. if min and max are commutable in which case the game has pure nonrandom optimal strategies). The optimal lower bound can be achieved via randomization between two pure strategies. In many practical cases we do not lose much by neglecting more complex strategies.

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ Bohr, Niels (1958). Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge. New York: Wiley. p. 38.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Heisenberg, W. (1927). "Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik 43 (3–4): 172–198. doi:10.1007/BF01397280.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Heisenberg, W. (1930). Physikalische Prinzipien der Quantentheorie. Leipzig: Hirzel. English translation The Physical Principles of Quantum Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1930.

- ↑ Kennard, E. H. (1927). "Zur Quantenmechanik einfacher Bewegungstypen". Zeitschrift für Physik 44 (4–5): 326. doi:10.1007/BF01391200.

- ↑ Schürmann, T.; Hoffmann, I. (2009). "A closer look at the uncertainty relation of position and momentum". Foundations of Physics 39 (8): 958–963. doi:10.1007/s10701-009-9310-0. arXiv:0811.2582.

- ↑ Tipler, Paul A.; Llewellyn, Ralph A. (1999). "5-5". Modern Physics (3rd ed.). W. H. Freeman and Co.. ISBN 1572591641.

- ↑ Feynman lectures on Physics, vol 3, 2-2

- ↑ Isaacson, Walter (2007). Einstein: His Life and Universe. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 452. ISBN 9780743264730.

- ↑ Gerardus 't Hooft has at times advocated this point of view.

- ↑ Likharev, K.K.; A.B. Zorin (1985), "Theory of Bloch-Wave Oscillations in Small Josephson Junctions", J. Low Temp. Phys. 59 (3/4): 347–382, doi:10.1007/BF00683782

- ↑ Anderson, P.W. (1964), "Special Effects in Superconductivity", in Caianiello, E.R., Lectures on the Many-Body Problem, Vol. 2, New York: Academic Press

- ↑ Gabrielse, Gerald; H. Dehmelt (1985), "Observation of Inhibited Spontaneous Emission", Physical Review Letters 55 (1): 67–70, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.67, PMID 10031682

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. An Introduction to Quantum Mechanics Pearson / Prentice Hall (2005).

- ↑ L. I. Mandelshtam, I. E. Tamm, The uncertainty relation between energy and time in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics, 1945

- ↑ DeWitt, B. S.; Graham, N. (1973). The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0691081263.

- ↑ Hirschman, I. I., Jr. (1957). "A note on entropy". American Journal of Mathematics 79 (1): 152–156. doi:10.2307/2372390.

- ↑ Beckner, W. (1975). "Inequalities in Fourier analysis". Annals of Mathematics 102 (6): 159–182.

- ↑ Szekely, G. J.; Rizzo, M. L. (2007). "The Uncertainty Principle of Game Theory". American Mathematical Monthly 114 (8): 688–702.

References

- Amrein, W.O.; Berthier, A.M. (1977), "On support properties of Lp}-functions and their Fourier transforms", J. Funct. Anal. 24: 258–267..

- Benedicks, M. (1985), "On Fourier transforms of functions supported on sets of finite Lebesgue measure", J. Math. Anal. Appl. 106: 180–183, doi:10.1016/0022-247X(85)90140-4.

- Bonami, A.; Demange, B.; Jaming, Ph. (2003), "Hermite functions and uncertainty principles for the Fourier and the windowed Fourier transforms.", Rev. Mat. Iberoamericana 19: 23–55..

- Folland, Gerald; Sitaram, Alladi (May 1997), "The Uncertainty Principle: A Mathematical Survey" (PDF), Journal of Fourier Analysis and Applications 3 (3): 207–238, doi:10.1007/BF02649110, MR98f:42006, http://www.springerlink.com/content/f7492v6374716m4g/fulltext.pdf

- Hardy, G.H. (1933), "A theorem concerning Fourier transforms", J. London Math. Soc. 8: 227–231, doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-8.3.227.

- Havin, V.; Jöricke, B. (1994), The Uncertainty Principle in Harmonic Analysis, Springer-Verlag.

- Heisenberg, W. (1927), "Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik", Zeitschrift für Physik 43: 172–198, doi:10.1007/BF01397280. English translation: J. A. Wheeler and H. Zurek, Quantum Theory and Measurement Princeton Univ. Press, 1983, pp. 62–84.

- Hörmander, L. (1991), "A uniqueness theorem of Beurling for Fourier transform pairs", Ark. Mat. 29: 231–240.

- Jaming, Ph. (2007), "Nazarov's uncertainty principles in higher dimension", J. Approx. Theory 149: 30–41, doi:10.1016/j.jat.2007.04.005.

- Mandelshtam, Leonid; Tamm, Igor (1945), "The uncertainty relation between energy and time in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics", Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR (ser. Fiz.) 9: 122–128, http://daarb.narod.ru/mandtamm/index-eng.html. English translation: J. Phys. (USSR) 9, 249–254 (1945).

- Nazarov, F. (1994), "Local estimates for exponential polynomials and their applications to inequalities of the uncertainty principle type,", St. Petersburg Math. J. 5: 663–717.

- Sitaram, A (2001), "Uncertainty principle, mathematical", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://eom.springer.de/U/u130020.htm.

- Zheng, Q.; Kobayashi, T. (1996), "Quantum Optics as a Relativistic Theory of Light", Physics Essays 9: 447, doi:10.4006/1.3029255. Annual Report, Department of Physics, School of Science, University of Tokyo (1992) 240.

External links

- Annotated pre-publication proof sheet of Uber den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik, March 23, 1927.

- Matter as a Wave – a chapter from an online textbook

- Quantum mechanics: Myths and facts

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- aip.org: Quantum mechanics 1925–1927 – The uncertainty principle

- Eric Weisstein's World of Physics – Uncertainty principle

- Fourier Transforms and Uncertainty at MathPages

- Schrödinger equation from an exact uncertainty principle

- John Baez on the time-energy uncertainty relation

- The time-energy certainty relation – It is shown that something opposite to the time-energy uncertainty relation is true.

- The certainty principle

![[p,x] = p x - x p = -i\hbar \left( {d\over dx} x - x {d\over dx} \right) = - i \hbar](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/586dfb7fa6dc5a9b076facd8d1eb3a70.png)

![\langle A^2 \rangle \langle B^2 \rangle\ge {1\over 4} |\langle [A,B]\rangle|^2](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/ea96244c63616b1e0a3d9e7868a90223.png)

![\sigma_A\sigma_B \ge \frac{1}{2} \left|\left\langle\left[{A},{B}\right]\right\rangle\right|](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/f8393ca8b47169c71f08ca74d35cce41.png)

![[A - \lang A\rang, B - \lang B\rang] = [ A , B ].](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/c12f985e7adaf649217b038c4c613295.png)

![\sigma_A \sigma_B \geq \sqrt{ \frac{1}{4}\left|\left\langle\left[{A},{B}\right]\right\rangle\right|^2

+{1\over 4} \left|\left\langle\left\{ A-\langle A\rangle,B-\langle B\rangle \right\} \right\rangle \right|^2}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/fa233527d3f84d7356824a9a9a448a8a.png)